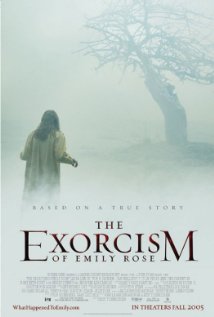

Scott Derrickson wrote and directed a modern horror classic with 2005’s The Exorcism of Emily Rose, a moody, atmospheric dyad of a chiller — a courtroom supernatural drama imposed upon by the “devil himself,” based upon an actual case of an exorcism gone wrong.

Derrickson’s follow-up, The Day the Earth Stood Still, which followed the pattern of the Spielberg-like “one for me, one for you” (a phrase derived from a filmmaker’s imposition to make a film based upon and primarily controlled by his or her own instincts, followed by a film controlled by a studio or distributor’s hankerings for profit), was a critical bomb. So, then, it was pondered, was Derrickson just a one-hit wonder, perhaps now just a film studio’s go-to boy for cash-and-dash remakes? Well, to say it bluntly, S.D.’s magic has returned … sort of.

To say Sinister is of the level of Emily Rose, or even better, would be a disservice to the complete horror of a film (I mean that in a good way) that Rose was. It had it all: fantastic performances from top-tier actors in Laura Linney and Tom Wilkinson, a fascinating premise, and the dedication to the “less is more” horror aesthetic — an aesthetic, I don’t care how many people disparage, is best served in the realm of true horror. Nothing, not even what the best filmmakers and FX people can create, will be as scary as your own imagination and the suspense that precedes the revelation, or lack of which, that will follow.

Sinister, Derrickson’s return to straight horror, is a massage of tropes. He’s recently stated in interviews that his three favorite horror films are The Shining, The Exorcist and The Changeling — three classics of scary cinema. So, it’s easy to see the influence these films have on his latest vehicle.

In Sinister, Ethan Hawke plays a one-hit wonder of an author. His first and best novel was akin to In Cold Blood, and revered as such. A true-crime novelist with a propensity to wreak upon himself the loath of local law enforcement for exposing their lackadaisical efforts in his books, we first find him moving himself and family into a new home, one in which a family of four was found lynched in the backyard with no applicable explanation. The fifth member of the family, a little girl named Stephanie, vanished the same night. Without his family’s knowledge of the deaths — his wife has an inkling, based upon Hawke’s previous efforts to assert himself into his subjects’ surroundings and circumstances of death — he begins to ascertain what exactly happened to this family, and where Stephanie may have vanished to.

He believes this case is his instance to reclaim his seat at the Capote literary throne he was once so cherished and admired for. With his family — a caring wife and two loving children, one a boy with night terrors, the other a daughter with a tendency to paint up her bedroom’s walls — on the verge of bankruptcy, this is his last ditch effort for fame, stardom and the eternal health of his family. There’s only one problem …

In his evidentiary search amidst the new residence, he comes across a mysterious box of super 8 film reels, reels that weren’t documented in the home’s attic upon its purchase. If you’ve seen the trailers then you know these films are the crux upon which the film pivots. In fact, the very first image of the film, before we even receive the minimal textual evidence that this a product of Hollywood, we see a segment of one of the grainy reels: a family of four getting strangled to death by a pulley/lever system enacted by a tree’s falling branch, with no suspect in view. In effect, the movie starts with a scene from a snuff film, one of the tropes I mentioned earlier that snuggles its way into this flick.

Hawke’s effort is that of a surrogate murder detective at first, but things go awry as he discovers more film reels that reveal not only other murders, but symbols, and ultimately, a sinister figure that lurks within the frames of the films in spurts, and only when adjusted and magnified with the use of modern technology (some of the murders go back decades). It’s only when he begins to investigate the symbols and ghostly figure within the films that he realizes he’s stumbled upon something more than human at work here.

While Derrickson eschewed the era of surprise gags and pop-up scares in Emily Rose (remember, less is more), he gives in here — perhaps influenced by the recent successes of Insidious and the atrocious The Devil Inside — yet he retains some of the slow churning boil of Rose’s efforts, a success that owes much to Hawke’s performance as he embodies Nicholson in The Shining (even wearing similar clothes) but with much more subtlety and compassion, and therefore, tolerance in his actions.

Yet, just as in The Shining, the themes of art and the price of its completion, compared to the price it incurs upon the familial artifact, are at work here. Also at work is Derrickson’s fascination with the filmic process itself: As Hawke shuffles through reels and reels of footage, he guzzles booze (another ode to The Shining and the price of artistry) and we endure extreme close-ups of the flicks, clicks of whirs of the super 8 projector’s mechanisms.

As we get closer to the truth of the situation, it becomes much more apparent that Derrickson’s film is more of an exercise in his  love for the genre and its history and eccentricities than an effort to top what could, and should, be called a horror masterpiece. And that’s okay. With the help of cinematographer Christopher Noll, who “shined his axe” most recently alongside the talented and experimental director Michel Gondry, Derrickson contains a well-tempered control of the camera, building tension with congested, naturally lit shots inside the home’s interior.

love for the genre and its history and eccentricities than an effort to top what could, and should, be called a horror masterpiece. And that’s okay. With the help of cinematographer Christopher Noll, who “shined his axe” most recently alongside the talented and experimental director Michel Gondry, Derrickson contains a well-tempered control of the camera, building tension with congested, naturally lit shots inside the home’s interior.

But, when the proverbial stuff hits the fan, and it’s the film chasing Hawke — and not the other way around — Derrickson and Noll let the camera breathe with some fantastic deep-focus shots that will make you wonder just what corner the evil will ooze out from.

While the ending may leave some yearning for something more, there’s no doubt that Derrickson has made a good, scary flick here. Not great, and not horrifying, but good, and worth a view.